Secondhand Textile Exports Should Be a Sustainable Practice, not an Environmental Disaster

We use the concept “waste colonialism” to refer to the flow of secondhand textiles and clothing from wealthy Western countries, such as the USA, EU, Australia, the UK, and Canada, to Africa, Latin America, and Asia. The main recipient countries include Kenya, Pakistan, Chile, and Ghana. The clothes are received in these countries as a charitable donations and legitimate trade in "used goods," However, opponents allege that in reality, moving these clothes from the wealthy countries to the less wealthy amounts to a form of externalization of the environmental, economic, and social costs of overconsumption and overproduction onto vulnerable communities that lack the infrastructure to manage the associated waste.

The waste colonization concept stems from the history of broader environmental racism and neo-colonialism. Historians contend that economically dominant global powers use it as a tool for exploiting others. This includes dumping pollutants on their soils. By doing so, they echo historical patterns of resource extraction and supremacy. The concept became clear in 1989, following the intensified targeting of emerging markets as dumping grounds for cheap secondhand items and hazardous waste. This emanated from the explosion of consumerism in the West.

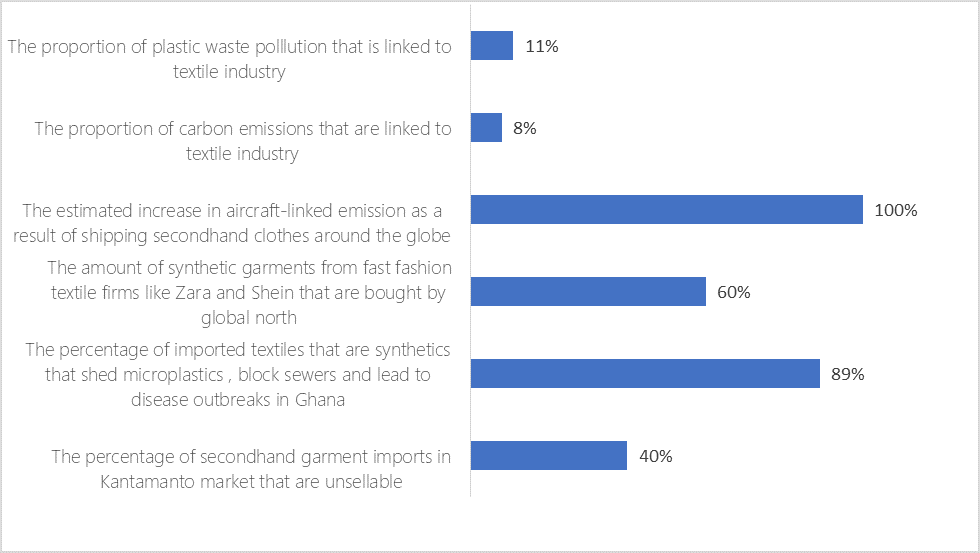

Regarding secondhand textiles, global brands like Zara, Shein, and H&M are popular for producing low-quality synthetic garments in the global north. The buyers of their products discard them quickly. These clothes are then collected, sorted, and packaged in bales. In one way or another, they find their way to Kenya, Ghana, Pakistan, and Chile, quality notwithstanding. In these destination countries, these clothes create new challenges. A remarkable percentage is unsellable. Additionally, the capacity of secondhand apparel markets to handle the waste is lower than the intake. Consequently, in many of the destination countries like Chile, clothes are hardly recycled, ending up as ugly mounds that take centuries to decompose and releasing carcinogenic microplastics to major water bodies.

| 24 billion units/~4.9 million tons | The size of annual secondhand cloth exports worldwide |

| $4.9 billion | The total value of secondhand textiles that were exported in 2022 globally |

| 92 million | The total annual global textile waste in tons |

| 2.3 million | The total number of tons of textile waste that move from the global north to the south annually |

| 700,000 / 1.7 grams | The number of microplastics fibers produced from a single wash of synthetic clothes |

| 500,000 | The approximated number of microfibers released from washing synthetic apparel globally in tons annually |

| 200,000–500,000 | Estimated annual number of textile-industry linked microplastics entering marine environments in tons |

| 200,000–200,000 | Approximate number of jobs lost since 2000 due to secondhand textile industry in Kenya |

| 100,000+ | Estimated number of jobs lost since 2000 due to secondhand textile industry in Ghana |

The proponents of shipping secondhand clothes to the global south view this process as a sustainable practice since they reduce demand for extractive activities, energy and recycling. Additionally, they claim that secondhand apparel is a major employment opportunity for the locals in the emerging markets.

As an illustration, various reports indicate that the industry boosted Ghana’s GDP by $76 million in 2023. As consumerism escalates in the wealthy North, the volume of the secondhand clothing being shipped to the South keeps ballooning. In isolation, the USA alone exported $830M worth of secondhand clothes to Africa under the African Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA). This is the USA alone. More of these clothes are exported by China, the UK, South Korea, and Germany. In terms of proportion, the USA, EU, and UK export 19%, 44% and 9% of secondhand clothes, while Pakistan, Malaysia, Kenya, and Ghana import 15%, 11%, 9% and 8% of the secondhand clothes, respectively. Twenty-five percent of these clothes end up in East African markets.

Conceptualizing the Problem of Waste Colonization

The perceived benefits of cloth recycling blur the reality of the damage that secondhand apparel presents to the recipient countries. Shipping of secondhand clothes has made destinations like Nairobi, Accra, and Karachi hotspots of solid waste pollution, and microplastics and toxic gas emissions. HyposSTAT Research Limited has documented these challenges as follows:

Solid Waste Pollution

The notion “waste colonialism” is linked to the negative externalities associated with shipping secondhand clothes from the North to the South. The shipping of these clothes is loathed because it promotes unemployment, solid waste, air, and water pollution in the areas they are destined to. In Ghana’s Kantamanto, which receives about 60,000 tons of secondhand apparel monthly, between 30% and 50% of the clothes cannot be sold because of stains, damage, or poor quality. These non-reusable consignments are usually incinerated or dumped in landfills. This is the main challenge in Kenya too, where secondhand clothes are referred to as Mitumba. In 2021, 10–15% of the 900 million secondhand garments that entered Kenyan borders ended up in landfills. The menace is exemplified in the Atacama Desert of Chile where massive used cloth waste mounds are an eyesore, taking centuries to decompose. Under these circumstances, the aid and trade from the North turns out to be a waste dumping scheme.

Air Pollution

On average, a garbage truck of secondhand clothes is either burned or dumped globally, releasing microplastics and other toxins to the environment and destroying habitats. Current estimates show that between 15% and 20% of the textiles in Kenya are burned in open pits. Open-air incineration compromises air quality by releasing furans, dioxins, and heavy metals, which are popular environmental hazards.

Water Pollution

In Ghana, between 20% and 30% of the beach plastic is textile fibers. Microplastics and dye runoff from bales leach into the oceans in Accra’s Korle Lagoon. The synthetic microfibers in the leach cause eutrophication, which leads to massive fish deaths. Local waste pickers are at risk of disease due to exposure to molds and chemicals. Thus, despite the popular view as a form of aid, the flooding of its related waste in the emerging markets is a major health hazard to millions of vulnerable people.

Exposure of Vulnerable People to Economic Hardship and Diseases

Shipping secondhand apparel from the north to Africa, Latin America, and Asia undercuts industrialization in the third world. It has led to the loss of hundreds of thousands of jobs, as indicated by the Kenya and Ghana statistics. Also, it has been established that these people are three times more likely to suffer from respiratory illnesses compared to the local average.

Major Findings

The labeling “waste colonialism” is bred in this cycle because the movements allow the Global North to maintain high consumption levels without bearing its full consequences, while the Global South bears the adverse consequences as a de facto dumping ground for secondhand clothes. The escalation of solid waste, air, and water pollution—which threatens marine life and human health—also undermines the livelihoods of vulnerable people in regions where second-hand clothes are shipped.

Contemporary Initiatives to Address Waste Colonization

Various stakeholders have embarked on measures to assuage the impacts of secondhand cloth dumping and their related adverse consequences. One of these is the extended producer initiative in France, where apparel brands pay between 0.05 and 0.12 euros as an eco-modulation fund per garment. This initiative helped raise 120 million euros in 2022. Another initiative is reverse logistics, by the producers. Zara and H&M have piloted a take-back to Europe initiative. In Ghana, the OR Foundation pays $0.20 for the lowest grade of secondhand clothes to finance upcycling. Rwanda banned secondhand cloth importation in 2018. East African countries proposed tariffs for these clothes between 2016 and 2019. Other initiatives include Chile’s restriction on low-grade bale imports in 2023 and the EU’s ban on unsorted textile second-hand items by 2025 under the EU Textile Strategy of 2022.

The Major Gap

Zara and H&M’s take-back in Europe exhibited a low uptake in the piloting stage. OR Foundation in Ghana managed to divert only 300 tons of waste in 2023. Rwanda partially lifted its secondhand cloth ban in 2023. The USA pressured East African countries to drop the secondhand cloth tariff initiative. Ideally, these patterns indicate a push and pull by various countries depending on their interests. Overlooking the adverse impacts of secondhand cloth shipping on destination countries depicts inconsideration for the fate of vulnerable people and insincerity to sustainability practices among the wealthy Westerners at the expense of the health and economic well-being of the South.

The Way Forward

Secondhand cloth shipping is both a sustainable challenge and a menace. The direction this takes depends on our capability to address the waste generated by the secondhand cloth shipping supply chain. To curb waste colonization, stakeholders across the supply chain—brands and manufacturers, governments and regulators, retailers and distributors, consumers, and waste handlers and NGOs—must take full ownership of this problem. Brand owners must shift from linear “take-make-dispose” models to closed-loop circular supply chains, where they account for every stage of the product’s full lifecycle, ranging from design, production, use, reuse, recycling, and disposal. Brands and manufacturers should lead by mandating take-back programs like the currently piloted Zara and H&M garment collection. Addressing the gaps that reduce the uptake of this model may prevent export dumping while generating funds for local recycling in origin countries. The brands should also create plans for 80–100% material recovery while keeping materials in high-value loops. Governments and regulators can aid these processes by building domestic recycling capacity and shifting costs to polluters by compelling them to fund national recycling infrastructure, subsidizing recycled ones, mandating full-lifecycle reporting, and penalizing non-compliance. Retailers and distributors can bridge the use and reuse gaps by partnering with producers for in-store drop-offs and offering discounts for returns. By collectively owning the full chain, stakeholders may dismantle secondhand waste generation, reducing the popularity of the waste colonization concept, fostering equity, jobs, and global health.